(Originally written 2017-10-07)

To most children of the nineties, “adventure game” was synonymous with “Sierra” and “LucasArts”. When you look at Sierra games like the King’s Quest, Space Quest, Police Quest, and Leisure Suit Larry series, you notice they’re all alike in one particular aspect beyond mere presentation, beyond the fact that they all control the same way: they are all third-person point-and-click adventure games.

Now that’s simplifying a little, since the earliest entries in those series weren’t point-and-click but instead had a text parser. But that doesn’t matter here, not very much.

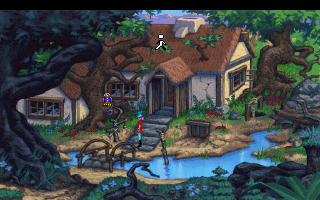

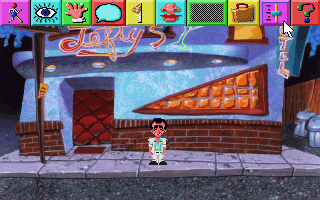

We have our background image, our animated main character (henceforth referred to as Ego, in keeping with the script code), other animated characters where called for, a mouse cursor, and the status line. In many Sierra games from King’s Quest 5 on the status line is blank. In earlier games it was not, often displaying the game name and player’s score.

Regardless, we can control Ego in a particular way, and by placing the mouse cursor on the status line, we can summon an icon bar:

Click a verb on the left half, then click somewhere in the game screen to act accordingly. Simple. The other three icons open your inventory, allow you to change settings and save/restore, and explain the other buttons. Almost all point-and-click Sierra games work like this.

The important question is, how much of all this is part of the engine, and how much is part of the game? Let’s find out!

As it turns out, the only common aspects that are part of the engine are:

- The ability to draw backgrounds.

- The ability to draw animated elements on those backgrounds, while also letting parts of it obscure them.

- The ability to play sound effects and music on a variety of sound hardware of the time.

- The ability to draw text.

- Mouse, keyboard, and joystick input.

- The ability to save and restore the game state.

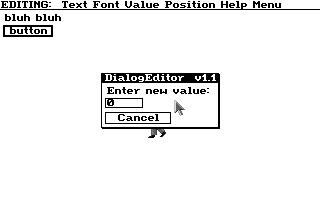

- A simple graphical user interface — windows, buttons, text fields and such.

- The ability to overrule the way windows look, to change their border style in script.

- The ability to draw a status line.

- The ability to tell how to go from one point to another, in various ways.

- For the later games, the ability to do various color tricks.

- For the old SCI0 games, the ability to use a pull-down menu bar.

- For the old SCI0 games, the ability to try and transform an English sentence into recognizable keywords.

That leaves this plethora as purely scripted:

- What an animated character is.

- What Ego is and what they can do that other animated characters can’t.

- What an inventory item is.

- How to respond to a click.

- What the icon bar is, and what buttons are on it.

- What a room is.

- What literally anything being an abstract “object” is. This covers a lot of ground.

- For the old SCI0 games, what goes into the menu bar and how to react to its use.

- For the old SCI0 games, how to invoke the text parser, and how to respond to its results.

The game code can’t tell if you’re using the 320×200 256-color VGA driver or the 640×480 dithered EGA driver, only the abstract “how many colors do we have”, or “how many voices can we play at once” instead of knowing that we specifically use the PC Speaker for music output, or the Roland MT-32.

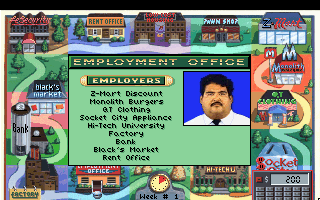

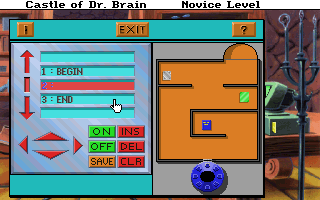

Those games I listed at the start are all third-person point-and-click adventure games because they all share a common set of scripts that define what an adventure game is. As such, not all Sierra SCI games are adventure games:

Sierra’s Creative Interpreter is not a third-person point-and-click adventure game engine, is what I’m saying.

You could remake Myst in it, after all. If you wanted.